Eels show up in a lot of ways in the illegal economies of medieval and Early Modern England. They were poached from creeks, stolen along the road, and pirated from ships. But eels were also an important part of the horse trade, where too-sharp horse dealers used them to help liven up older, broken-down horses.

Among the tricks of the trade was something called “feaguing,” which Francis Grose, in his 1785 Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, says means “to put ginger up a horse’s fundament, and formerly, as it is said, a live eel, to make him lively, and carry his tail well.”[1] Grose goes on to note that the practice was so wide-spread that “a forfeit is incurred by any horse-dealer’s servant, who shall shew a horse without first feaguing him.”[2] We still have the phrase “to ginger up a horse,” but before they used ginger, shady horse merchants used eels.

Eels may not have been a commonly-used tool anymore by Grose’s day, but earlier English writers spoke of them with more familiarity. The humorist poet Edward Ward, in his 1700 “A Song Upon Dancing,” wrote that dancers “skip with nimble force / As Eels i’th’ belly of a Horse / Which Jockies use each Market-Day / To make ‘em dance, as People say.” [3] Ward, like Grose, may be professing a lack of first-hand knowledge – it depends on what his “as People say” refers to – but he at least seems to believe that it was happening in his day. Writers from the previous century certainly were even more sure.

A young John Milton made reference to feaguing in his ribald 1628 Latin poem Prolusion VI, in a section mocking his fellow Cambridge students. In reference to “certain Irish birds” (aves quaedam Hibernicae) he says that they are “more useful to grooms because they are by nature lively and brisk and prancing, and if they were forced into the anus of scraggly horses would make them livelier and quicker than if they had ten live eels in their bellies.”[4] Milton’s statement is far more affirmative than Ward’s, and he was not alone in speaking about feaguing with eels as common practice.

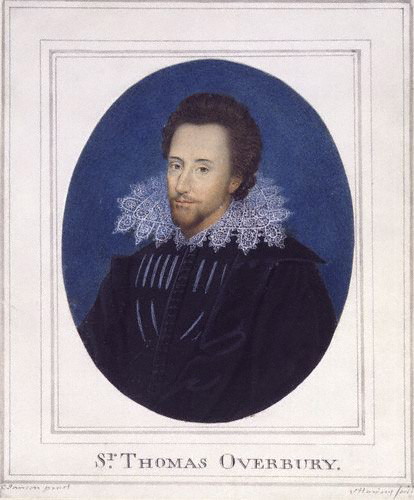

In 1616, friends of the famously late poet and politician Thomas Overbury republished his most well-known work, the poem “Wife,” along with an array of poetic caricature sketches of unsavory types of people written by anonymous authors.[5] One of those poems detailed the characteristics of “An Arrant Horse-Courser,” and noted that (among other unsavory habits) the man knows how cover up diseases and defects of all sorts. “For powding his [the horse’s] eares with / Quicksilver, and giuing him suppositories / of live eels he’s expert.”[6] As with Milton’s poem, there is no “as is said” or “formerly” in this description, and the author does not put distance between himself and what he portrays as an established practice. Nor, for that matter, does he mention ginger, or other instruments for feaguing horses that appear later.

At the start of the seventeenth century, it seems, eels were the way you spirited up a horse for sale. And everybody from university students to the king’s councilors knew – or, at least, believed – it to be true.[7]

Notes

[1] Francis Grose, “Feague,” in Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (London, 1796).

[2] Grose.

[3] Edward Ward, The Dancing-School with the Adventures of the Easter Holy-Days. (London: J. How, 1700), 6. Italics in original.

[4] “Has igitur arbitror agasonibus utiliores futuras; nam cum sint naturae vividae vegetae et saltaturientes, si equis strigosis per podicem ingerantur reddent eos protinus vivaciores et velociores quam si decem vivas anguillas in ventre haberent.” John Milton, “Prolusion VI,” in Latin Writings: A Selection, ed. and trans. John Hale, Bibliotheca Latinintatis Novae (Assen: Van Gorcum & Comp., 1998), 88. Hale, the editor, seems unfamiliar with feaguing, because he makes a note to say that, at this point, Milton’s comparisons are becoming “almost surreal and magical.”

[5] Overbury’s death in 1613 became an enormous scandal in its day. He expired while a prisoner in the Tower of London, and it eventually came out that he had been poisoned at the direction of a court conspiracy that included Overbury’s best friend, the friend’s married love interest, and King James himself. The lurid tale involved political intrigue, lust, infidelity, money, and betrayal, and essentially reads as a work of bad historical fiction.

[6] Sir. Thomas Overbury, “An Arrant Horse-Courser,” in Sir Thomas Ouerburie His Wife with New Elegies Vpon His (Now Knowne) Vntimely Death : Whereunto Are Annexed, New Newes and Characters / Written by Himselfe and Other Learned Gentlemen. (London, 1616), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A08597.0001.001/1:4.50?rgn=div2;view=fulltext. Amusingly, the author writes that, though everyone falls victim to these ministrations, they work best on Frenchmen, who are especially gullible.

[7] Historical descriptions of the practice leave some questions about its mechanics unanswered. They will remain unanswered here, save to say that translations of Milton that go with “suppository” miss the full force of his description.

3 responses to “Feaguing Before Ginger: A Lively Horse Discussion”

So part of me wants to know how this was done but a much bigger part doesn’t.

Frankly, me to.

[…] Before the 1800s, feaguing was usually done with a live eel, often mentioned in poems written in the 1700s. In his 1700 poem A Song Upon Dancing, Humorist poet Edward Ward writes that dancers skip with nimble force, like eels in a horse’s belly, which Jockeys use each market day. At Grose’s publication, eels were soon replaced by ginger. (Source: Historiacartum) […]